Butter Me Up! Edible Fats And Oils, And Their Spread-Ability

Rheology makes up the bread and butter of our work, which can provide a wealth of insight into the physical handling behaviour of edible fats and oils like butter and margarine. One of the most important qualities of a good spread is (perhaps unsurprisingly) its ability to spread easily.

Ideally a good spread is soft enough that there is little resistance to applied deformation but strong enough that it maintains its shape and doesn’t run-off the surface it has been spread onto. In this study we’ll be looking one test that can quantify two the rheological properties contributing to the spread-ability of butter, vegetable margarine and olive oil margarine.

If you’d like us to talk you through other appropriate tests for comparing spreadability feel welcome to contact us.

Rigidity and Strength of Structure

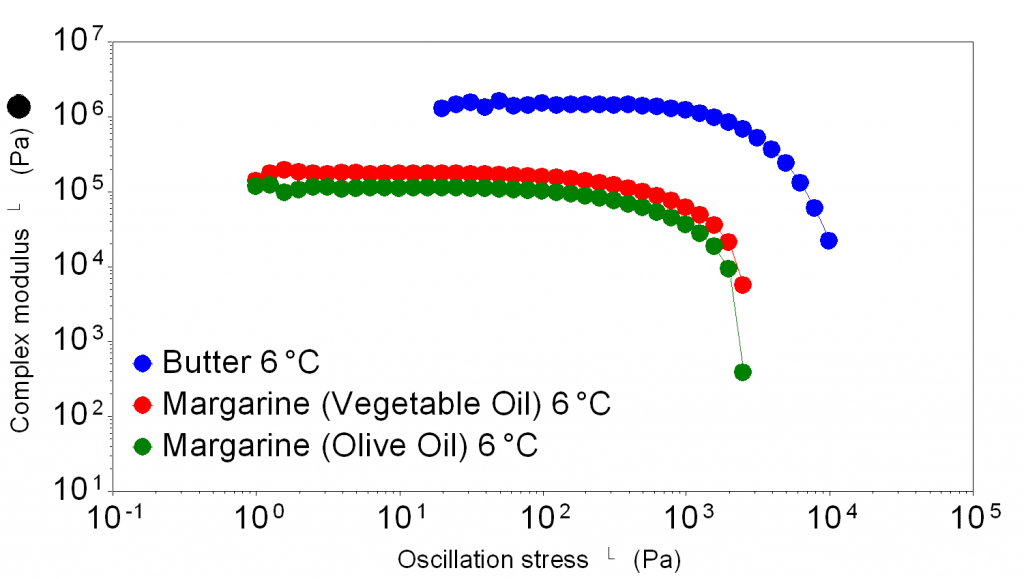

Rigidity, stiffness and elasticity – all of these properties can be measured by a gentle wobble from our rheometer. Oscillatory testing looks at the response of a material to gradually increasing sinusoidal stresses, looking for an elastic response (the bounce-back-ability of the material). We use two useful metrics from this test to describe the aforementioned properties.

Complex modulus can be thought of as the overall resistance to deformation – a high value is likely to manifest as a more stiff or rigid material (like a fresh carrot) in comparison to a product which has a low complex modulus which will wobble like a jelly. In the oscillatory stress sweep above, we see a plateau value at low oscillation stresses indicating the spreads are deforming elastically; the sample will return to its original shape after the stress has been removed.

Eventually the increasing stress will exceed the material’s ability to respond elastically, and the material will deform ‘plastically’ , at a point known as the material’s ‘yield stress’. If a material has a higher yield stress, it takes more effort to permanently deform.

The high yield stress of butter in comparison to either the vegetable or olive oil margarine, makes it much more difficult to deform and subsequently spread. The margarines are pretty similar, but the olive oil margarine appears marginally easier to work with.

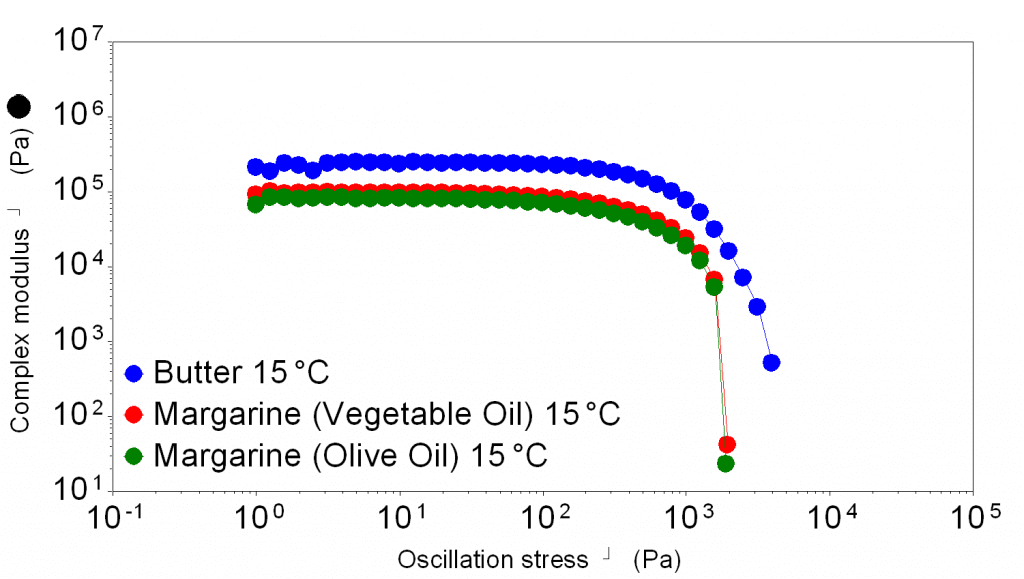

Effects of Temperature

The fats in these emulsions are particularly sensitive to temperature, an increase in temperature to 15°C causes the spreads to become more pliable. Butter decreases in its rigidity by as much as a factor of 10 times. The shape of the yielding behaviour of butter also changes showing a much more gentle curve compared to the steep drop at 6°C – permanent deformations can be achieved earlier with less effort.

We’re big fans of the repeatability and sensitivity of oscillatory testing, and while a great start there is a wealth of other tests that can help explore properties such as stickiness and glide.

To learn about using viscosity profiling, tribology and axial compression testing of edible fats, contact us now.